Getting around Delhi pre-2002 would have looked very different from how it does now. For any resident of the Delhi region, a life without the metro system seems unimaginable today, yet there was a time when such a system didn’t exist - and prior to the opening of the first line in 2002 one had to make do with crowded buses for mass transport. Today, the Delhi metro covers a massive network spanning 393 km spread over 288 stations, and is among the world’s largest, and also among the world’s busiest metro systems. In fact, to facilitate better connectivity in the region, it is only set to expand further and is expected to help reduce the usage of personal automobiles, to help with the severe air pollution problem the region faces, especially in the winters.

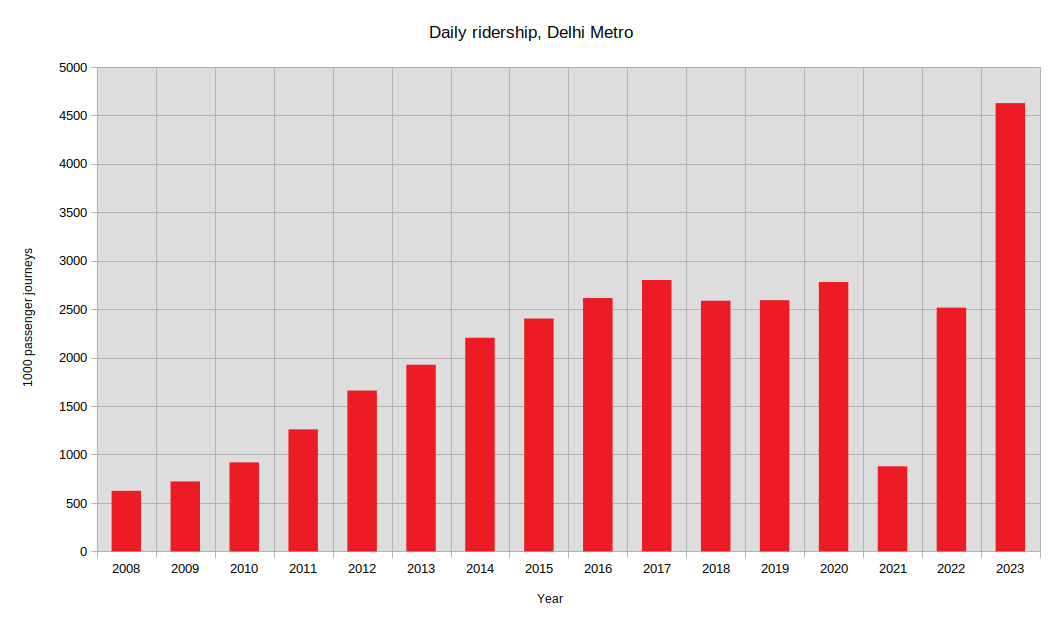

Delhi Metro usage over the years

Delhi Metro usage over the years

What makes a metro “successful”?

The Delhi Metro Rail project has clearly been a massive success, and it has made the lives of the residents and visitors to the region much easier by providing a reliable and quick means of transport to various destinations in and around Delhi. The word “success” is used quite loosely here but broadly speaking, without getting into the financial aspects, we can define the “operational” success of a metro rail along the following parameters:

- Timeliness: Are the metro services running at the frequency they are intended to run, or is there a significant delay in arrival times?

- Reliability: Is the average downtime because of maintenance, breakdowns, etc. within the defined system specifications?

- Passenger load: Each system is designed keeping in mind a rated amount of usage in terms of passengers carried on a daily basis. So if there are too few passengers, it means that the system is underutilized, and people don’t see any value in using the metro - but if there are too many, it means the designed capacity is being exceeded and it could cause breakdowns and unexpected consequences - in which case, there need to be more services added whether in terms of frequency or number of coaches. Either of the two extremes would make the system “unsuccessful”, but the former is arguably a bigger cause for concern.

But is it cost effective?

The financial perspective is certainly important as well, as these projects are generally expensive to fund, and any delays in construction can escalate costs by great amounts - but a more fundamental concern is whether the metro is performing the function it is intended to perform, i.e. carrying a significant number of passengers in a quick, predictable manner. If this basic criterion is not met, then looking at the financies seems almost useless - there is no way a metro project will be able to deliver financial returns if it isn’t even able to ferry a minimum number of passengers, as all the sources of revenue depend heavily on this figure - be it in the form of ticket sales, advertisements, retail space, restaurants, or other commercial spaces that can be rented out.

This perspective is also crucial because even if a metro ferries a lot of passengers and is very reliable (“successful”), if it is not able to sustain itself financially through its various channels of revenue, it would burden the government significantly over time, and this would further be passed on to taxpayers. Eventually, the metro will have to compromise in terms of quality, number of services, or will have to cease operations completely on lines that bleed money.

Rapid growth in India’s metro network

In the Indian context, these factors are very important to consider given the rapid increase in the number of metro systems constructed over the past few years as part of the Indian government’s boost to infrastructure development (the “PM Gati Shakti” plan) for enabling the economy to grow. While it is heartening to see that the government has great intentions of providing a means of mass rapid transit to people in various cities all over the country, at the same time it is also imperative to raise concerns about their effectiveness - some of these metro systems are certainly necessary, but are they all? Is this the best (or even a decent) way to spend the rather tight budget the government has? While there are some financing plans specified in the metro policy of 2017 to fund these projects (e.g. with loans from JICA), some number crunching is certainly needed to establish a cost-benefit tradeoff.

One can see that prior to 2014, there were 4 operational metro systems throughout India - and today, this number stands at 17, a considerable increase in the visibility of metro systems all around the country, clearly highlighting the current government’s focus on metro development - and it is set to grow further, as the government intends to further construct at least 15 to 20 more brand new metro systems in many other cities.

A part of the Namma (Bengaluru) Metro under construction

A part of the Namma (Bengaluru) Metro under construction

While a lot of these metro systems play a very important role in the daily commute landscape, especially in crowded cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Chennai, and Kolkata, one needs to evaluate more carefully the effectiveness of metro systems in other cities. While one can also argue that since the metro systems in smaller cities are not mature yet - that is, they do not have enough of a “network” to be actually useful and are all currently with just one or two lines - one still needs to consider the question seriously whether constructing metro systems is the best option or not.

Construction justified?

A key element here is also the visibility aspect - when a brand new metro line is constructed, it looks like a new “feature” of the city, rather than just a routine upgrade, and the government gets some points to boast about how it is providing new infrastructure to the public. And as mentioned before, in many cases, metros are really useful - but in other cases, it does seem like a simpler, rather “dull”, option, like more electric buses, or carefully planned bridges and underpasses would have sufficed.

It is difficult to assess in many cases whether there really is a long-term master plan involving a number of interconnected metro lines in a city based on its projected future expansion, or if metro lines are constructed just as a gimmick for short-term political brownie points. In any case, the bottom line is that there are lots of expensive metro systems constructed, without any reliable cost-benefit analyses available, and the current ridership of many of these systems is far below what the projections suggest.

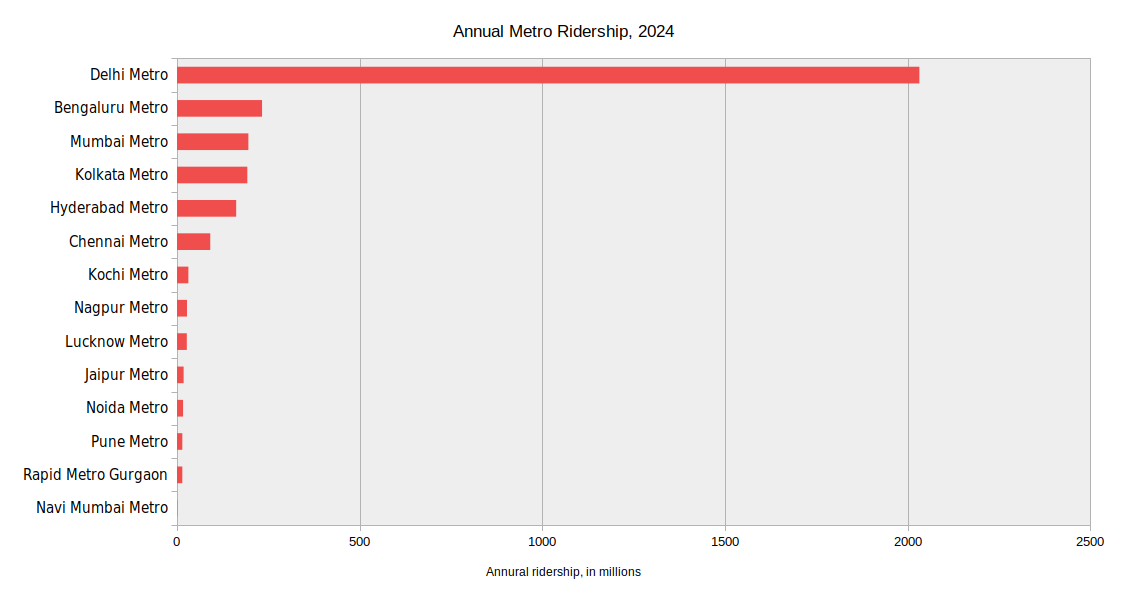

Annual ridership among various metros in India

Annual ridership among various metros in India

Projects may be launched with much fanfare, but they can be deemed successful only if they stand the test of time - for instance, the Mumbai Monorail project was launced with a lot of hype and excitement as the first monorail system in India, and an extension was also carried out - but all it takes is one visit to any of the stations along the Jacob Circle to Chembur stretch to see how much of a ghost line it has turned out to be; one can even go so far as to say that the city was better off without this monorail line. There are plenty of projects like this one which could have had better upfront analyses, even after taking into consideration the fact that it is difficult to make accurate projections.

What should we do with these metro systems?

Now that so many metros are already constructed, what’s the next step? If it is really evident after the passage of time that they simply don’t find any use among commuters, some tough decisions will have to be made - one cannot simply shut them down, or even worse, demolish them arbitrarily.

But what can be done is that a robust survey can be carried out involving diverse commuters to know what their pain points are, and if any reasonable modification to the existing metro line can address them (for instance, providing feeder buses at certain stations) - or if any crucial metro link can be added which would prompt them to use the metro. Additional ways of generating revenue can be explored, like station naming rights, more efficient use of the premises, etc. However, if there really is enough evidence that the metro cannot be made financially sustainable, and the losses are too high, a tough decision about ceasing operations may have to be made; there could still be some exploration of converting the stations into commercial spaces, as that area still has some value. There are other innovative ways too of still making the space useful to the public, like in New York City.

The main assumption in this post is that it is not clear what the overall plan for all the metro systems in India really is. Going by how things have been so far - either one has to merely trust the government’s words, going by this response to The Economist’s article - or have a healthily critical view of the sudden boom in the construction of new metro systems all over the country.