“Democracy” is a word one would certainly have come across if they had taken an interest in their civics classes during their primary schooling years. For a majority of the world, democracy is the standard system of government, and is quite often taken for granted. For many, it is just a normal part of daily life, without the question raised, of how things might have evolved through the course of history for systems and institutions to get to where they are - whether people like them or not. Though general trends point towards more countries becoming democratic, they don’t imply that countries are becoming more democratic; these trends can always change.

In this post, we’ll talk about a concept that is closely linked to democracy, but not necessarily the same: elections.

More specifically, we’ll talk about elections in India, and what kind of voting systems would be appropriate in the current demographic context. Considering the open nature of ideas, there can be so many designs for electoral systems - but not all of them would make sense in every setting. In the local Indian context, some options can certainly be explored that would make the “voice of the people” arguably stronger.

But first, we need to clear the air a bit about the words “elections” and “democracy”.

Elections and Democracy

One would be tempted to think that elections and democracy not only are closely related, but that one implies the other - but that is not always true. Since “democracy” literally means rule (“kratos”) of the people (“demos”), a democratic system would at the very least mean that there is some collective voice of the people echoing through the government they elected. There are several ways in which it can be - and arguably, is, mostly - flawed (e.g. through gerrymandering, heavy polarization, or disenfranchisement of women voters in the past), but the bottom line is that there is at least some collective public voice that can realistically effect a change of government.

There is no dearth of places where elections are not held at all, and we won’t go further into that discussion since the topic is not relevant for the discussion of voting systems. What is interesting, though, is that there also exist several examples of places where elections are certainly held - but the result is “somehow” already known beforehand, and a transfer of power is either extremely unlikely, or even impossible - such that people’s expression of candidate choice is rendered irrelevant, thus eroding the “demos” from democracy. There are several means to achieve this setup - whether through media capture, flawed institutions, widespread disinformation, or any other way - but the point to note is that democracy is not a given, and can slide backwards if left unchecked.

Without getting into the normative view of democracy, if one were to ensure that democracy should be maintained in a given context, the fundamental aspect to consider is the robustness of elections in that particular context. And that means not only ensuring that elections are held in a free and fair manner, but also having a voting system that truly represents the voice of the people with regard to their candidate choice (there are also some radical options like a “lottery-based democracy” but for this post we shall restrict ourselves to a democracy involving the casting of votes). It can be debated further that one can also vote for “issues” or “ideas” rather than candidates, but that is a separate matter and requires its own different discussion.

Considering that we are restricting ourselves to the Indian context, we first need to understand the baseline of the voting system in India.

The Electoral System in India

All elections in India in which people elect their representatives follow a “first past the post” (FPTP) system, in which each of the constituencies has only one representative, and who is selected if they receive the highest number of votes during the election - basically a plurality, not necessarily a majority. For each constituency, a list of candidates is drawn up by the Election Commission of India based on the nominations filed by the candidates, whether as independents or as members of a party.

Once the list is finalized, on the voting day, people eligible for voting can go to their allotted polling booth and cast only one vote for their choice of candidate. Irrespective of how close the votes cast may be, there is only one candidate that wins per constituency. Once all the winning candidates are finalized, the “majority” can form a government - this majority is formed either by the winning candidates belonging to a single party, or through a coalition of multiple parties and/or independents depending on negotiations related to conditions for entering the government.

The advantage of this system is that it is quick, stable, and simple - people express their choice, and the candidate with the highest number of votes wins…so what’s the problem?

Well, there are plenty! In no particular order, there’s so much to think about:

- Constituencies and their boundaries: Constituencies are defined based on the population census, and in principle need to be redrawn based on changes in population through a “delimitation exercise” so as to reflect the ground reality of voters. But such a change is mired in political conflict (e.g. if a particular state government is able to slow down its population growth through effective policies, it is “punished” by getting fewer seats because of delimitation), and is prone to gerrymandering to favour the ruling government. Moreover, how a constituency boundary is drawn cannot be decided easily, as it is an open question in a way, with several possible answers (e.g. geographical features, historical reasons, or maybe even arbitrary)

- Non-representation of the majority: Because of the way the current FPTP voting system is designed, a candidate can get as little as 25% of the votes in a constituency and still be the winner, if the voters are highly fragmented in their voting preferences. This would mean that only a minority of the voters would truly be represented in the legislature, with the majority feeling disenfranchised, since their choices were “wasted” - and when this notion is scaled to the entire country, it really feels like the majority can be rendered voiceless. There are several examples of Indian elections wherein parties with as little as 30% of the total cast votes got the majority of seats!

- Unfairness towards closely finishing candidates: Considering the scale of the elections, vote counting is sometimes not precise - and it so happens that candidates can end up with really close finishes (e.g. someone getting 49.8% of the votes as against the winner getting 50%). In such cases, it feels rather unfair that just because of a handful of votes (whether because of miscounting or not), someone entirely loses an opportunity to represent a significant number of people. In cases where a close runner-up could have been acceptable as the second preference for a majority of the voters, the existing system creates sub-optimal outcomes

- False binarization: In a country as large as India, whether in terms of size or population, there is a massive plurality of voices and opinions. Though in the state legislative assemblies, there is a considerable number of regional parties that represent local interests, when it comes to the national level, the choice realistically ends up between two major parties or groups. To have their voices heard at the national level, regional parties end up having to form coalitions with larger parties with heft, and regardless of their leverage, the compromise for the regional party is much more in terms of having to deviate from the promises made to the people and having to adapt to the national coalition. This undermines the rule of the people in a way, since the people would have voted for the regional party based on their regional interests, but then because of the coalition’s compromise, would have to spend the next few years being unheard till the next elections show up

- Incentives for short-term thinking: Knowing that a candidate or a party only has to secure the highest number of votes in a given constituency rather than a majority of the votes, the election system favours a setup in which the incumbent can appeal to the existing voter base by launching and completing projects that “look” great, rather than making structural changes and compromises that would span much longer timelines and benefit the larger public in that constituency. In a voting system which has a possibility of runner-up candidates also being elected, the incentives change, and a larger section of society has their interests represented

There could be many more issues with the existing system (e.g. dynastic politics being favoured because of broad family appeal) but at the end of the day, it is relatively simple to implement at scale, and when it was established there also needed to be a sense of stability of elections in a newly independent country. It is still the system of the land, and we have to follow it until electoral reforms are made.

What Can Be Changed?

All said and done, though we can’t change things as we wish, we can still have our own thoughts on possible electoral reforms! With recent technological advances and maturing of India’s democracy over the last several decades, there can be many alternatives to consider, without having the concerns and constraints from 1947-50, when certain difficult choices had to be made to hold some stability of governments.

Basically, we would want certain fundamental “requirements” about elections to be met:

- A representation of people that is good enough: we wouldn’t want a situation like the current one, wherein in many cases only a plurality (say, even 20% of the popular vote) rather than a majority (> 50%) suffices to win in a constituency - thus making a large proportion of votes “wasted”, and thereby compromising representation. But at the same time, we need a form of representation that is “good enough” i.e. a considerable majority of votes corresponding to what people prefer, rather than a perfect representation

- Stability: If the elections produce candidates that are too “fragmented”, i.e. there is no sense of compromise and agreement among the elected representatives, then a government is prone to collapsing before the end of the term - if it is formed in the first place. Hence we would ideally want an election system that would lead to a “stable” set of representatives who can compromise and collectively make decisions, holding a government together. The current FPTP system works well in this regard, and probably was chosen in the initial days of the nation’s independent existence to maintain stability

- Implementation feasibility: The chosen election system should be feasible to be implemented on a large scale - in terms of availability of personnel, awareness of voters, technological limitations, and so on. An election might be simple by design, but implementing it in a country with a billion voters is by no means a straightforward task

Considering these three basic requirements, we can look at some perspectives on voting systems.

Number of Representatives

Currently, there are 543 Members of Parliament to represent the people of India at the national level - and one would think that that is a good enough number - considering that people’s interests are also represented by Members of Legislative Assemblies at the state level (and thus, plenty of people involved in legislation). However, we live in a federal system, wherein each state is (in principle) its own little country of sorts and has its own ideas - so issues local to the state do require their fair share of attention - but they are of a completely different nature than questions to be addressed at the national level. We do need more voices representing the people, and 543 members representing a billion and a half people sounds rather inadequate.

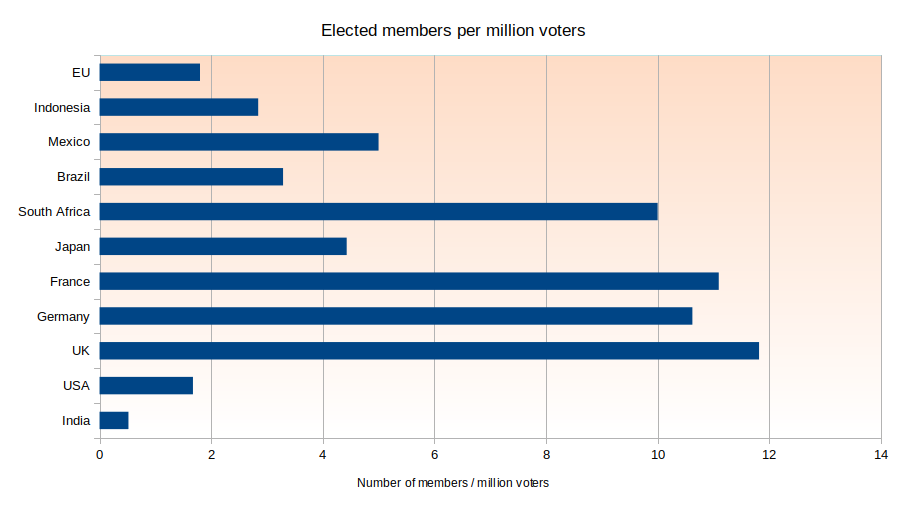

We can perform a quick comparison of this number in large democracies around the world. Though this is a very crude comparison considering that political and voting systems across countries are so varied, it still indicates something very fundamental - that there are too few elected members to represent the people of India at the national level:

Comparison of number of elected representatives in the legislature across various countries/blocs

Comparison of number of elected representatives in the legislature across various countries/blocs

There is certainly a lot to gain by adding more representatives in the Lok Sabha, be it through a higher diversity of opinions or more representation of the people. How effective a legislature becomes by just increasing the number is certainly debatable, but in any case, based on crude comparisons, it can be argued that the state of India’s legislature would increase in “quality” with a greater number of representatives.

Proportional Voting?

In many countries around the world, a system of proportional voting is followed. Roughly, it means that a political party gets a number of seats proportional to the fraction of votes it gets.

This works well in theory since it means that people’s diverse views are echoed directly through the elected representatives - but in an extremely diverse country like India, a move to proportional voting would also lead to a highly fragmented Parliament - and that would mean really difficult negotiations on the smallest of decisions. Even with the existing FPTP system, elected representatives in coalition governments find it difficult to come to a compromise; making it more fragmented for the sake for perfect representation would bring lawmaking to a standstill, and high instability for the government.

Additionally, proportional voting would also mean that the interests of certain groups would dominate the concerns of the Parliament sheerly because of the population distribution of voters. A large number of people would have to make great compromises in their standpoints, and that could lead to great mistrust in the Union government. So even though proportional voting leads to “perfect representation”, it may not serve well from the perspective of the functioning of a government.

Single Transferable Vote?

Currently, legislative assembly elections in India are quite simple, in that there is no concept of voters indicating their candidate preferences, or quotas for deciding winners - each voter casts one vote, and the candidate with the highest number of votes in a constituency wins from that constituency. However, this distorts the representation of the voters, and it can be changed to accommodate a single transferable vote (STV) system.

In this STV system, a voter votes only once, but in their vote can optionally indicate an order of preferences for other candidates in the constituency. The maximum number of winning candidates has to be fixed - if we say that there can be up to three winners from a constituency, then the minimum fraction of votes per candidate has to be 25% - and once the quota is reached, the candidate is declared to be “elected”, and surplus votes for that candidate are distributed to the candidate who was preferred second in those votes. This process is repeated till there is no more “transfer” of votes possible, and there could be three winning candidates, depending on the preferences indicated by voters. However, based on the voting patterns, fewer candidates may also be selected - so getting a fixed number of winning candidates from a constituency will require some modifications, like a mixed-system.

Thus, this system, though a bit more complicated, allows voters to express a sense of compromise and can avoid complete polarization or splitting of the vote base, and thus incentivizes competing political parties to appeal more broadly to the general population.

The implementation of this system would have been difficult in the past considering the intricacies of “rounds” for calculating winners and losers, but with modern technological tools, this should be possible. There are many practical challenges to consider, of course, but the changes required to enable such a system of voting are not radical, and can be rolled out through pilot projects first.

Two-Round System?

Many countries make use of a system in which two rounds of voting take place to choose representatives. In the first round, a large pool of candidates is considered, out of which (usually) the top two “proceed” to the next round of voting, and then the public makes their final choice out of these two candidates.

Since people are given the opportunity to express their choices first, and eventually made to exercise their votes among two candidates that the highest number of voters think worthy of being elected, this system inherently adds a sense of compromise - and is hence quite “democratic” in its approach. Though representation is not perfect, it is quite adequate. There is a suprising amount of coordination that can take place strategically between the rounds to produce vastly different end results, as exemplified by the 2024 French legislative elections.

Though this system can work well in the Indian context, it comes with the massive challenge of conducting two rounds of voting, and that may not be practically feasible, considering that conducting one rounds of the general election with FPTP is also quite a difficult feat to achieve. Adding more personnel may help to some extent, but asking a billion voters - many of whom live far from their constituencies - to travel twice to cast their votes, is asking for trouble.

To Conclude: Starting Simple

Electoral systems are certainly an interesting topic to study and simulate, but when it comes to making choices that affect real people and their ability (whether directly or indirectly) to function properly, things get really difficult. This post was only a collection of thoughts about electoral systems in India, but all things considered, the following choices about electoral changes seem quite reasonable:

- Increasing the number of elected representatives in the legislature: We certainly need more representation, and increasing the strength to ~1500 would be a good start. Naturally, that means changing the procedures of parliamentary functioning (for instance, one speaker for 1500 MPs would find it difficult to manage the assembly) - but those details can be worked out with elaborate discussions. However, it also depends on the delimitation exercise, since without accurate information about voter distribution, further decisions about constituencies cannot be taken.

- Creation of three-member constituencies with an STV system: This will be consequential in terms of determining who gets elected, and will probably produce results far different from the existing system’s. The technology that is in place can be used to support this form of voting without drastic changes, since the main change would involve reprogramming of existing machines to accommodate preference selection during the vote casting. But more importantly, a strong election awareness campaign will have to be run to make voters aware of this new idea of expressing candidate preferences rather than selecting just one candidate. There will have to be some deliberations, though, about the exact method to use for declaring winners, since STV could lead to a variable number of candidates being declared winners, and that could have major ramifications.

- Retaining FPTP at the state level: State-level elections have a different focus compared to national-level elections, and the representation of people’s national interests is not boosted by changing the state’s election system. Hence, the existing system of FPTP can be kept “as is” for state-level elections - but there is certainly a need for delimitation of constituencies based on population changes.

- Performing studies on voter behaviour across the country: Though the election commission publishes statistics related to elections, there is no solid programme to assess whether the voting system is effective in terms of people feeling represented or not. There could be several collaborative studies involving academic and government institutions for understanding voter preferences and concerns, and the electoral system could accordingly be periodically modified to elicit trust among the general public. This would go a long way in ensuring a robust democracy, and for people to feel a sense of confidence in constitutional authorities like the Election Commission of India.

There are several aspects about elections in India that can be considered for making changes - right from the method of selection of ECI officials, to the means of voting, to the phasing of elections, to enforcement of the model code of conduct, and on and on - but the fundamental idea of how voters express their preferences is very crucial to the functioning of democracy in India.

It is high time that the people of India got a refreshing new way to choose their elected representatives, and retain the “demos” in democracy as solidly as possible in this ever-evolving and ever-changing world constantly trying to curb the Voice of the People.